- Home

- Annette Hess

The German House Page 11

The German House Read online

Page 11

“That’s perfectly all right. I would do the very same in your husband’s position. I’ll be back for Henning in half an hour.” Annegret left the room. The moment she stepped into the corridor, the smile vanished from her face. I have to stop doing this, she thought, and not for the first time.

AT LUNCHTIME, most of the people involved in the trial went to the cafeteria in the municipal building. Members of the prosecution, spectators, witnesses, and family members chose between meatballs in caper gravy or goulash and ate at long tables in the impersonal, utilitarian space. Some of the defense attorneys, including the White Rabbit, also carried around their trays, searching for a spot. A group of defendants sat at a table to the side and satisfied their hunger like everyone else. People either ate in silence or spoke in low voices about the weather forecast, the terrible traffic, or the meat, which was generally considered dry or even rubbery. Eva took her tray to a table the other girls—the secretaries and stenotypists—had occupied. A rosy young lady in a pale suit, whom Eva had seen before at the public prosecutor’s office, smiled at her in welcome. Eva sat down across from her and began to eat the meatballs, which her father would never have allowed to leave the kitchen, lukewarm as they were. Eva didn’t have much of an appetite, anyway. Another two witnesses had testified before lunch, and both were from Poland. They had, however, spoken German well enough to testify without Eva’s help. Still, Eva had sat by them, to provide assistance if needed. She’d only had to translate a single word: canes. Because that’s what SS officers had carried on the ramp, instead of cudgels, to give new arrivals a sense of security when they stepped off the train. But if anyone spoke, asked a question, became defiant, or if children started crying—then the canes were used as clubs till quiet was restored. Both witnesses had seen Defendant Number Seventeen on the ramp. One of the witnesses also identified the main defendant, who denied as unequivocally as the pharmacist, ever having been at that place. Let alone having performed any of those so-called selections. Eva looked at the table across the cafeteria, enveloped by a cloud of cigarette smoke. She thought the defendants had all sounded like they were telling the truth. They all seemed surprised. Incredulous, almost incensed that one could think them capable of looking into people’s mouths and squeezing their biceps, and separating the able-bodied individuals from their relatives, tearing families apart forever. They convincingly denied sending those deemed useless straight to the gas chambers. Eva set aside her silverware. Ten thousand people a day. That’s what the witness Pavel Pirko, who’d been in a work unit responsible for cleanup on the ramp, said. Eva scanned the room for the mischievous little man, whose testimony was as animated as if he were recounting a boat tour on the Rhine. She couldn’t find him. All she saw was David Miller at the other end of the room, quickly and carelessly shoveling food into his mouth and addressing a colleague with his mouth full. Eva tried to visualize it: ten thousand women, children, men. Ten thousand weakened humans, who climbed one after the other into trucks and were driven off. The only thing she could imagine, however, was their hope for a warm shower and a piece of bread.

ON BERGER STRASSE, Eva’s mother, Edith, had gone downstairs to the laundry room, her arms laden with German House’s dirty linens. She stood before the new machine in her blue checkered smock and watched the first wash cycle. The closed white box pumped and thumped, as if a big heart were beating inside. Edith couldn’t break away from the sight, although she had plenty to get done in the kitchen. She had a vague sense that a new age was waltzing in. Or better yet, lumbering in, she thought, remembering how this monstrosity had required three men to carry into the cellar. Every Tuesday up till today, she had boiled aprons, tablecloths, dishtowels, and napkins in a large tub, stirred and churned them with a long wooden paddle, and finally drawn the soaking wet laundry from the lye, which made her eyes tear. Now she stood here and had nothing to do. She felt useless and sighed. Her hair was starting to thin and go gray, her body was losing its shape, becoming blurred, softer, weaker. Some nights, before putting on her face cream, Edith would sit in front of the mirror and pull her skin back, till her face appeared as smooth as it once had. She would sometimes skip dinner for days, to fit back into her velvet skirt. But then more creases would appear on her cheeks. At a certain age, every woman’s got to know whether it’s a cow or a goat she wants to become! Edith read that once in a women’s magazine. Her mother had indisputably turned into a goat. Edith couldn’t decide. She could be either onstage. And more: mistress, daughter, mother, grandmother. With makeup and a wig, she could play Lady Macbeth, Juliet, Schiller’s Joan of Arc. . . . Her thoughts were interrupted by the sound of the cellar door opening, and Ludwig came in wearing his white chef’s coat.

“What’s keeping you, Mother?”

Edith didn’t respond, and Ludwig could tell she was processing something inside. Just like the new washing machine.

“The whole point of that gadget there is to make use of your time elsewhere.”

“I always liked doing the laundry, I liked stirring the vats, I liked scrubbing on the washboard, and I liked beating and wringing out the wash. I don’t know if I’ll ever get used to this thing.”

“Sure you will. Now come on, you left me in the lurch up there with my potato salad.”

Ludwig turned to go, but then Edith said, “Don’t we need to talk to her?” Ludwig looked at his wife and shook his head.

“No.”

Edith was silent for a moment while the drum inside the washing machine spun faster and faster on its axis. Whoom-whoom-whoom. “He lives in Hamburg now. He’s a businessman and owns a really big company.”

Ludwig knew immediately whom Edith meant. “How do you know that?”

“It’s in the paper. And his wife, she’s in the city too.” The washing machine hissed loudly and then began to pump, gurgling. Husband and wife gazed at the appliance in silence.

AFTER ANOTHER EYEWITNESS HAD BEEN HEARD, who as a thirteen-year-old had seen her mother and grandmother for the last time ever on the ramp, the chief judge adjourned court for the day. Eva headed for the ladies’ room, where she had to wait for an empty stall. There was a line of women, like at the end of a theater production. Missing today, though, was the lively chatter all about how who had performed. The mood was restrained, and the women politely held the doors open, passed the towel, and acknowledged one another with a nod. Eva felt dazed herself. When a stall freed up, she locked the door and had to pause for a moment to recall what she was doing there. Then she opened her briefcase and pulled out a folded, pale-patterned dress. She took off her dark skirt, her blazer. It was tight in the little stall, and she kept bumping into the walls. As she pulled the dress on over her head, she nearly fell over. She swore under her breath and contorted her body reaching between her shoulders for the zipper, which she finally managed to zip up. The restroom emptied out in the meantime, and silence fell outside the stall door. Eva folded her work clothes and tried to fit them into her briefcase. She couldn’t get the clasp to fasten, though, and left the bag open. She was about to leave the stall, when she heard the restroom door open. Someone entered, sniffled, maybe even cried. Then blew her nose. There was a faint smell of roses. A tap was turned on, and the water rushed. Eva waited behind the door, hugging her briefcase and holding her breath. But minutes passed, and the water was still running. Eva opened her stall door and stepped out.

The wife of the main defendant stood at one of the sinks, washing her hands. She was wearing her little felted hat again, and her dark brown handbag was on the windowsill. The woman dabbed her blotched face with dampened fingertips. Eva stepped up to the second sink beside her. The woman didn’t look up, but her body stiffened. Evidently Eva was now her enemy. Side by side, they washed their hands with curd soap that didn’t foam. Eva peeked out of the corner of her eye at the woman’s wrinkled hands and thin, worn-out wedding band. I know this woman. She once slapped me. With that very hand, Eva thought, and was startled by the absurd idea. She shook it off,

turned off the faucet, and turned to leave. The woman abruptly blocked Eva’s way, while in the background the water continued streaming.

“You can’t believe everything they’re saying in there. My husband told me all they want is restitution—they want money. The worse the stories they tell, the more money they get.”

The woman retrieved her purse from the windowsill and before Eva could say anything, she had left the ladies’ room. The door closed with a snap. Eva looked at the running water and turned it off. She peered into the mirror and touched her cheek, as though feeling the memory of a blow she had received a long time ago.

After retrieving her coat, hat, and gloves from the coat check in the almost deserted foyer, Eva stepped out of the municipal building. It was just before five. The daytime gray had transitioned into the bluish gray of twilight. The headlights of passing cars threw long bands of light into the evening haze. The municipal building was on a busy street.

“You did well today, Fräulein Bruhns.” Eva turned around. Standing behind her was David Miller; he was smoking and, like always, not wearing a hat. Eva smiled in surprise at the sound of praise coming from his mouth. “The lead prosecutor told me to tell you that.”

David turned away and joined two other men from the prosecution, who had just left the building. Eva hung back, feeling somewhat snubbed. Why did this Miller fellow go out of his way to be rude to her? Was it because she was German? He didn’t appear to take issue with anyone else, though—at least not his colleagues. Or the stenotypists.

EVA’S THOUGHTS WERE INTERRUPTED by the sounds of honking. Jürgen’s yellow car had pulled up beside the row of parked vehicles. He left the engine running, jumped out, and opened the passenger door for her. Eva climbed in. In the car they kissed each other quickly and bashfully on the mouth. After all, they were engaged. Jürgen merged into traffic. Eva, who normally provided the lively, disjointed commentary of a child about what she saw to the left and right on the street as they drove, remained silent. She seemed blind to the people walking home at this hour, weighed down with shopping, dragging their children by the hand past the illuminated shopfronts that kept catching their attention. Jürgen looked over repeatedly, as though searching for a visible change, a mark that the day had left on her. But her appearance was unaltered. Then he asked, “So, you nervous?”

Eva turned to face him and couldn’t help but smile. She nodded. “Yes.” Because they had a plan that felt almost forbidden.

Twenty minutes later, Eva had the feeling the car was entering a different world. They passed through a tall, white metal gate that swung open and then closed behind them, as if by magic, and then followed the curves of an endless-seeming driveway dotted with squat lampposts. Eva squinted into the darkness, past the trees and bushes that were still bare, and detected an expanse of lawn beyond. She thought of how perfect it would be for Stefan to play soccer. And she thought of the two big flowerpots her father lugged up from the cellar every spring, which her mother filled with red geraniums and set outside to decorate the entrance to the restaurant. The house emerged suddenly in the darkness. It was long, modern, and white. It seemed as impersonal as a garage, which Eva found strangely comforting. Jürgen pulled up in front and briefly took her hand.

“Ready?”

“Ready.”

They got out. Jürgen wanted to show her his house, which would soon be hers as well. Jürgen’s father and Brigitte were still on their island in the North Sea. And as they took their daily seaside walk before dinner, bracing themselves against the gale, they never suspected that at the same time, their son was leading his blond fiancée through the rooms of the family estate. Jürgen even opened his father’s austere but tastefully appointed bedroom for Eva. She was overwhelmed by the number of rooms, the liberality, the elegant colors. She gazed up at the high ceilings, which had been important to his father, Jürgen explained, because he needed space above his head to think. Eva’s heels alternated between clicking brightly on the smooth marble floors and sinking deep into the thick, cream-colored wool carpet. The pictures on the walls also made a much different impression on Eva than the Friesian landscape at home. She studied the painting of a house composed of severe forms bordered in black, beside a weirdly erected lake, which had been painted wrong on purpose. That much was clear to Eva. She thought of her cows at home. When she was six or seven, she had given them all names. Eva tried to remember them and recited to Jürgen, “Gertrude, Fanni, Veronika. . . .”

“Good evening, Herr Schoormann. Fräulein. . . .” A buxom, middle-aged woman in a beige housedress had entered the room. She was carrying a tray with two filled flute glasses. Jürgen took the glasses and handed one to Eva.

“Frau Treuthardt, this is Eva Bruhns.” Frau Treuthardt, with her slightly bulging eyes, stared openly at Eva.

“Welcome, Fräulein Bruhns.”

Jürgen held a finger to his lips and said “Shhh” to her. “This remains a secret. Today is a first, unofficial visit.”

Frau Treuthardt screwed up her eyes, which was probably meant to be a sly wink, and flashed a row of small, healthy teeth. “By all means! I won’t make a peep. I’ll tend to dinner now, if that’s all right.” Jürgen nodded, and Frau Treuthardt turned to leave.

“Is there anything I can do to help in the kitchen, Frau Treuthardt?” Eva asked courteously.

“That’s all we need, our guests having to cook for themselves!” Frau Treuthardt left the room.

Jürgen, amused, told Eva, “She’s a little rough around the edges, but she does her work very well.”

The two clinked glasses and drank. The tingly cold liquid was dry and tasted of yeast to Eva.

“It’s champagne,” Jürgen said. “Now, how would you like to see the height of decadence? Bring your glass.”

Eva was curious and followed Jürgen. They crossed a tiled corridor to the “west wing,” as Jürgen sardonically called it. The unsettling odor, which Eva had noticed the entire time and thought was her imagination, grew stronger. Jürgen opened a door, turned on the ceiling lights, and Eva stepped into a huge room tiled in sky blue. The swimming pool. A long glass front made up the sidewall to the right and provided a view of the dark green lawn. A couple of scattered outdoor lamps created hazy coronas of light. It looks like a poorly maintained aquarium, Eva thought, that hasn’t held any fish in ages. By contrast, the water in the pool seemed pristine. It sat there untouched, its surface gleaming.

“Would you like to take a dip?”

“No, no thank you.”

Eva was in no mood to change her clothes and get wet. Jürgen seemed disappointed.

“Jürgen, I don’t even have a swimsuit.”

In response, Jürgen opened a cabinet that contained at least five options on hangers. “That shouldn’t be a problem. I’ll leave you alone too.” Eva again tried to protest, but Jürgen continued, “To be honest, Eva, I’ve still got a call to make, which might take a while. You’ll find swim caps in the shower over there.”

Jürgen pulled a suit off its hanger, handed it to Eva, and left. Eva was alone. She noticed little bubbles floating to the surface from the bottom of the pool. Like the sparkling wine in her hand. Oh, right, it’s not sparkling wine. It’s champagne. Eva took another sip and shivered.

Ten minutes later, Eva—wearing the pale red swimsuit, which was a bit tight—climbed down the metal ladder into the pool. She had painstakingly stuffed her thick hair into the white rubber cap and obediently took one rung after the other. She created small waves, and the water surrounding her was warmer than she’d expected. When the water reached her breasts, she let go of the ladder and began swimming. She turned onto her back. Hopefully the swim cap would hold. When Eva’s hair got wet, it took half an hour to blow-dry. Eva spread her arms and legs, lay at the surface, and gazed up at the humming tube lights on the ceiling. How odd, swimming in an unfamiliar house. With expensive champagne in her belly. In a bathing suit that wasn’t hers. Eva had never felt less able to imagine leaving

her old life to live here with Jürgen. But that was the way things worked. Eva thought of Jan Kral, who might already be on his way home. At this very moment, he might be flying away in an airplane high above the house with the swimming pool, going back to Poland. By way of Vienna. Eva had taken this trip once herself, two years earlier, to an economic congress in Warsaw. That’s where she had lost her virginity. Eva rolled onto her front and dove down into the water. She swam to the bottom of the pool and could feel the water slowly seeping into her swim cap. But she stayed under till she could no longer take it.

Jürgen paced silently on the thick carpet in his office. He wasn’t on the phone—he had lied to Eva. He didn’t have a call scheduled. Jürgen wanted to know what it felt like to have Eva here, next door, somewhere, in a different room, but not be able to see her. What would it feel like when she was living here with him? He had to admit, it was nice knowing Eva was in the house. Like a small new organ pumping fresh life into an old body.

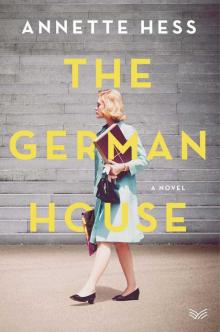

The German House

The German House